Finding Solace in Sade

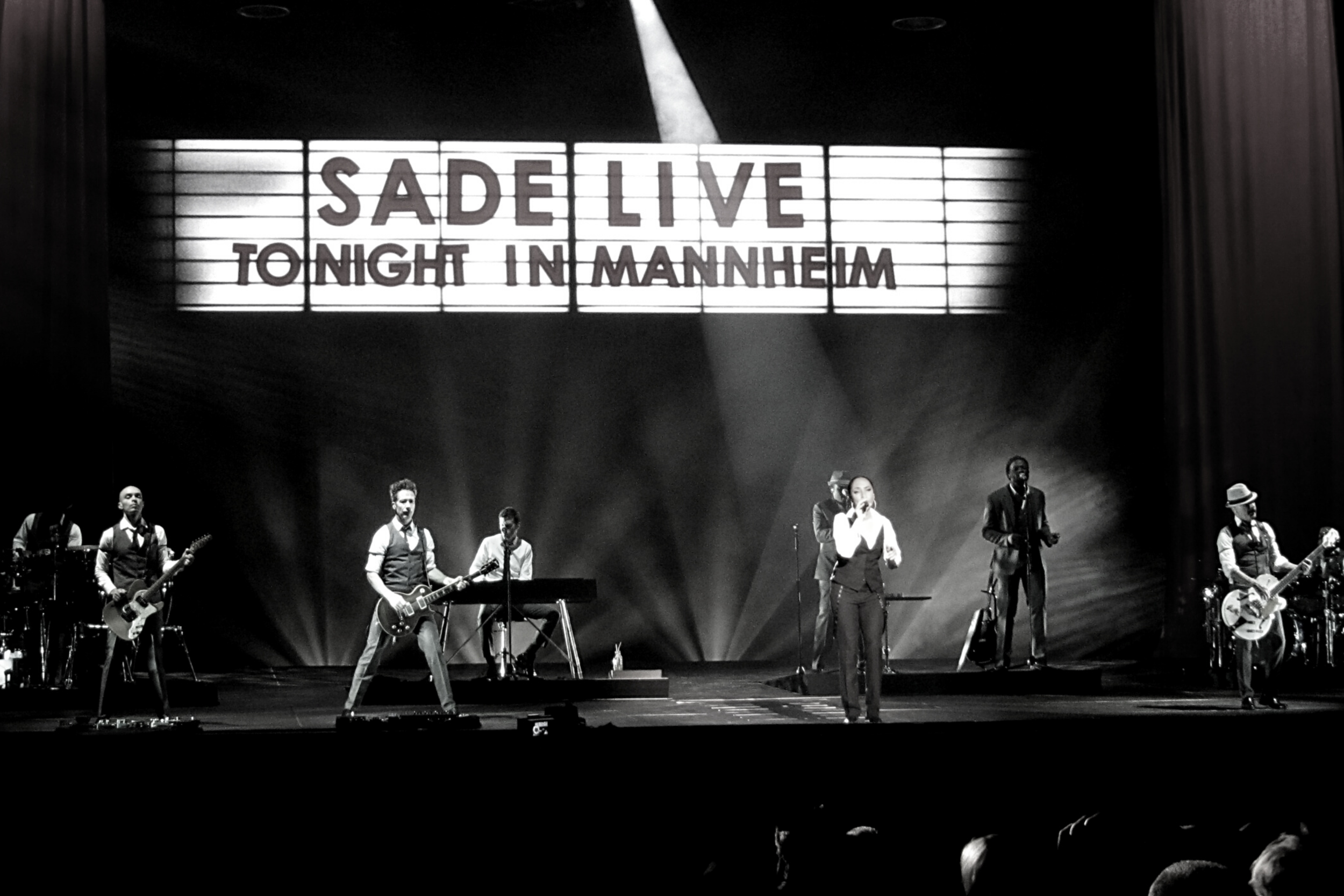

Thilo Parg / Wikimedia Commons

On a quiet Sunday afternoon, a summer thunderstorm gentles into showers then stops entirely, and the steel ball of tension that’s found a home in my chest dissipates just as gradually. Sunlight starts to arc over the rain-soaked pavement, and Sade’s honeyed voice settles over the room: cherish the day / I won’t go astray / I won’t be afraid / you won’t find me running. For a moment, I don’t want to run, either—despite the hours and hours I’ve spent between these four walls, I want to stay right here in the midst of a song unearthing whatever beauty remains around me.

Outside the window, a middle-aged couple walk past, shaking out raincoats and plastic grocery bags clutched in white-gloved hands as they speak to each other from under the masks plastered to their mouths and noses. But don’t bristle at the aberrations, Sade seems to say—no, catch hold of the love they pass between them instead, leaning into each another on the emptied street, blinking against the newborn sun.

There’s a generosity about Sade, a glowing and golden-toned invitation to still, and to notice, for just a few minutes. In the days following my personal rediscovery of their music I found myself listening for hours on end, in times of contemplation or creation as well as in busier moments. Without harsh overtures or too many instruments, this melody makes no insistent demand on your attention but manages to claim it all the same.

/

The term “easy listening” bothers me, as if it implies that the music in question is less worthy or complex simply for its soothing appeal. But many have used it in reference to Sade—as Jacob Bernstein writes in a 2017 piece for The New York Times, you once upon a time might have stepped into a record store and found their albums in the easy listening section. It wouldn’t be an entirely inaccurate descriptor. They are easy to listen to, stretched-out syllables and elegant instruments melding with seemingly little effort. But such apparent ease is only a testament to Sade’s skill: it’s extraordinarily difficult to make the kind of deep and lasting impression, to touch as many listeners as this band has over their decades-long tenure in the music industry.

There’s something special in how Sade surrounds their audience in a pocket of warmth, allowing a listener to slip into whatever fantasy has caught their fancy that day. All the same, it’s not quite escapism for which I, at least, turn to the band. No doubt the silk-soft vocals, the saxophone and synths are as seductive as they are transporting. And yet, Sade has never been interested in shying away in their lyrics from exploring the weight of injustices historic and current.

In the song “Pearls” on their 1992 album Love Deluxe, for example, the band documents the emotions of a woman fighting to survive with her family during the Somalian civil war (the title refers to precious gathered grains of rice). “Immigrant” from Lovers Rock (2000) recounts the racism and xenophobia faced by an immigrant to a new land. And rather than distracting us from the pathos in these lyrics, Sade makes pain the centerpiece: showing us how bearing witness to the tragedy of history is a beautiful and necessary act in itself.

Even beyond amplifying the narratives of other underrepresented and marginalized identities, Sade’s songs often powerfully articulate the experiences of their lead singer and songwriter, Sade Adu. As a Black working-class woman who began in the music industry during the 1980s, there’s no question that Adu faced an uphill battle in establishing herself as an artist. But the music she makes cannot be stripped of her identities or politics: a listener is made aware always of the creator and force behind the art they’re consuming.

In “Slave Song”, Adu sings from the perspective of an enslaved person praying for a different world and envisioning the generations of their people to come. In doing so, Sade pays homage to the history of an art created for the survival and hope of Black people that then turned around to enslave them. In the song and music video for “King of Sorrow”, Sade depicts the plight of those for whom each day is a monotonous struggle to survive in a harshly capitalistic world—where they are valued only so far as they remain pliant cogs in the machine, and punished for any digression from that impossible ideal. The D.J.’s playin’ the same song / I have so much to do, I have to carry on / I wonder, will this grief ever be gone? Sade croons, and it hits just the right note—a sentiment specific yet universal, resonating amongst so many of us finding a new rhythm in this strange, pandemic-ridden world.

/

I have found myself struggling to reach calm, to carve space out of sickness, as I’ve faced the last few months. Almost unintentionally, I flit between social media, news outlets, and phone calls to family hundreds of miles away which only barely hold panic at arm’s length. My experience is neither a singular nor a defining one, as so many people across the world right now face not just emotional upheaval but sudden and terrifying physical and financial distress.

For the first few weeks I couldn’t even concentrate on music, despite its constant presence in my life up until now. Somehow it felt trite to seek emotional comfort; I couldn’t help but berate myself for not instead refreshing news websites or calling to check on another family member. It was only to fill the silence between frenzied phone calls and 6 o’clock breaking news bulletins that I pressed play on a Sade album to which I’d never before listened all the way through. It was purgative to rediscover my love for the band. Much like the first time I’d found them in my late teens, I didn’t quite dive into their discography so much as let it wash over me, a cooling solace for the too-big concerns that usually punished me relentlessly. The only way I could get to sleep for a few days was by playing their music before settling into bed.

And I began to understand that, just as I wasn’t alone in feeling suddenly adrift and incurably frantic, I also wasn’t alone in seeking out pockets of serenity in Sade’s music. One need only open a Youtube video of any one of their songs to find, alongside detailed lyric dissections and praise for Sade Adu’s beauty and style, dozens of listeners in the comments discussing how the music is getting them through this period. Is anyone else listening to this in quarantine? one commenter asked, and reading all the replies to the affirmative brought me a rare warmth. I don’t know that I can quantify or explain this trend—but then, maybe I don’t need to. After all, catharsis and comfort have always gone hand in hand.

/

A few weeks into the pandemic, the horrific murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers—as well as a host of other incidents of police brutality and killings of Black people—incited protests all over the United States and the world. Living in a city where thousands have taken to the streets to stand against these injustices has been a transformative experience. This is what hope looks like, step by step, voice by voice.

There is a heat to this time, something electric: we’re at once in the midst of a deadly pandemic and the enduring crisis of racism. Yet from within the vortex something new has emerged—a solidarity forged by fire, a determination to turn this crucial moment into a movement. Sade’s music might not be directly subversive or obviously revolutionary. But the band encourages care in a way few other artists do: care of the community as well as of the self, which are, of course, inextricably linked. The comfort Sade brings me serves in many ways as a desire to move and tend to my communities in the same way I myself have been moved and tended to. It’s a soundtrack to a quiet fight, a battle anthem for the reality we’re trying to create—one of compassion, one of liberation.

On a practical note, non-Black people all have a duty to step forward and offer their support to this cause in whatever way possible. In that vein, a few places I would suggest for donations: The Okra Project, Bail Funds for Protestors, and the Emergency Release Fund. One of the organizations on the ground, Reclaim the Block, has also made a great list of other funds and organizations in Minneapolis needing donations right now. And if you’re unable to take to the streets or help monetarily, this document describes many actions you can take besides donating and protesting.

In an interview from 1992, Sade Adu noted that “sadness in songs is positive because it brings it out of you; it brings the sadness out. It’s not that the song makes you feel sad, the sadness is already there. The song just makes you recognize it.” That sense of recognition soars in the music that her band offers to its audience. In helping so many of us name our own permutations of fear and grief, Sade proves why we reach for them as we face sickness and strife, recast our world in a more just mold, do our best to look to the sun and—instead of running—choose to stay.