"To mourn is also to acknowledge the limitations of language." (Gavin Yuan Gao on Elegy)

Gavin Yuan Gao (they/them/xe) is a contributor to Half Mystic Journal’s tenth issue, elegy. They are a poet and translator based in Brisbane, Australia. They hold a BA in English and Creative Writing from the University of Michigan. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in New England Review, The Journal, Waxwing, Best New Poets 2021 and elsewhere. Their debut poetry collection, At the Altar of Touch, is forthcoming from the University of Queensland Press in 2022.

We asked three of our Issue X contributors for their personal definitions of elegy: how it’s formed, where it’s been, what it could be. Here is Gavin Yuan Gao’s vision of the last dropped petal—the mirror in mourning—the light still on for what was once beautiful…

I lost my toothbrush cup while moving house two years ago. It was given to me by my mother, who taught me how to brush my teeth. She passed away after a brief battle with a terminal illness when I was five. The plastic toothbrush cup was the sole surviving witness to my first attempt to care for myself, a rite of passage to independence in a child’s otherwise unremarkable life.

I spat my first loose baby tooth in it. I carried it with me across three continents and three decades. It was the fisherman’s knot that held together the eras of my life. When the realization of its loss sank in, I was inconsolable: I felt a whole history abruptly erased. It was as if the memories of my life’s most meaningful moments were a set of perfectly arranged snooker balls into which someone had shot the white cue ball and sent everything scattering. Nothing else could prove those moments had once belonged to the same person.

/

The longer I live, the more I am inclined to believe that the primary condition of life is loss. An elegy, by its most ancient, rudimentary definition, is a mourning song. To mourn is to memorialize, resist oblivion, refuse erasure of the past. Any traumatic event—be it the passing of a loved one, the death of a friendship, or the loss of a sentimental item—tears a hole in the fabric of us. The center of the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves is destabilized.

To me, writing an elegy is a regenerative process through which we might begin to reconceptualize and reshape our relationships with those we have lost. In this sense, elegy is the most natural response to loss. It is a means of surviving a life disrupted by grief, though it is no remedy.

Language fails to represent the true magnitude of our suffering, nor is it capable of restoring memory. I will never be able to replicate with words all the sensory details associated with the lost toothbrush cup: the exact hues and texture of the watercolor triptych of a toy circus printed on its side, the touch of my mother’s hand on my wrist as she corrected the angle at which I held my toothbrush, or the elation in her voice as my baby self finally mastered the art of brushing. To mourn is also to acknowledge the limitations of language.

/

I wrote “The Maestro,” my poem in Half Mystic Journal’s tenth issue, for my maternal grandfather, who passed away last year after a stroke. Though the poem imagines otherwise, I wasn’t by his side in his final days. In retrospect, rewriting the scene was the only way I could move my relationship with my grandfather beyond the overwhelming guilt I felt in the wake of his death.

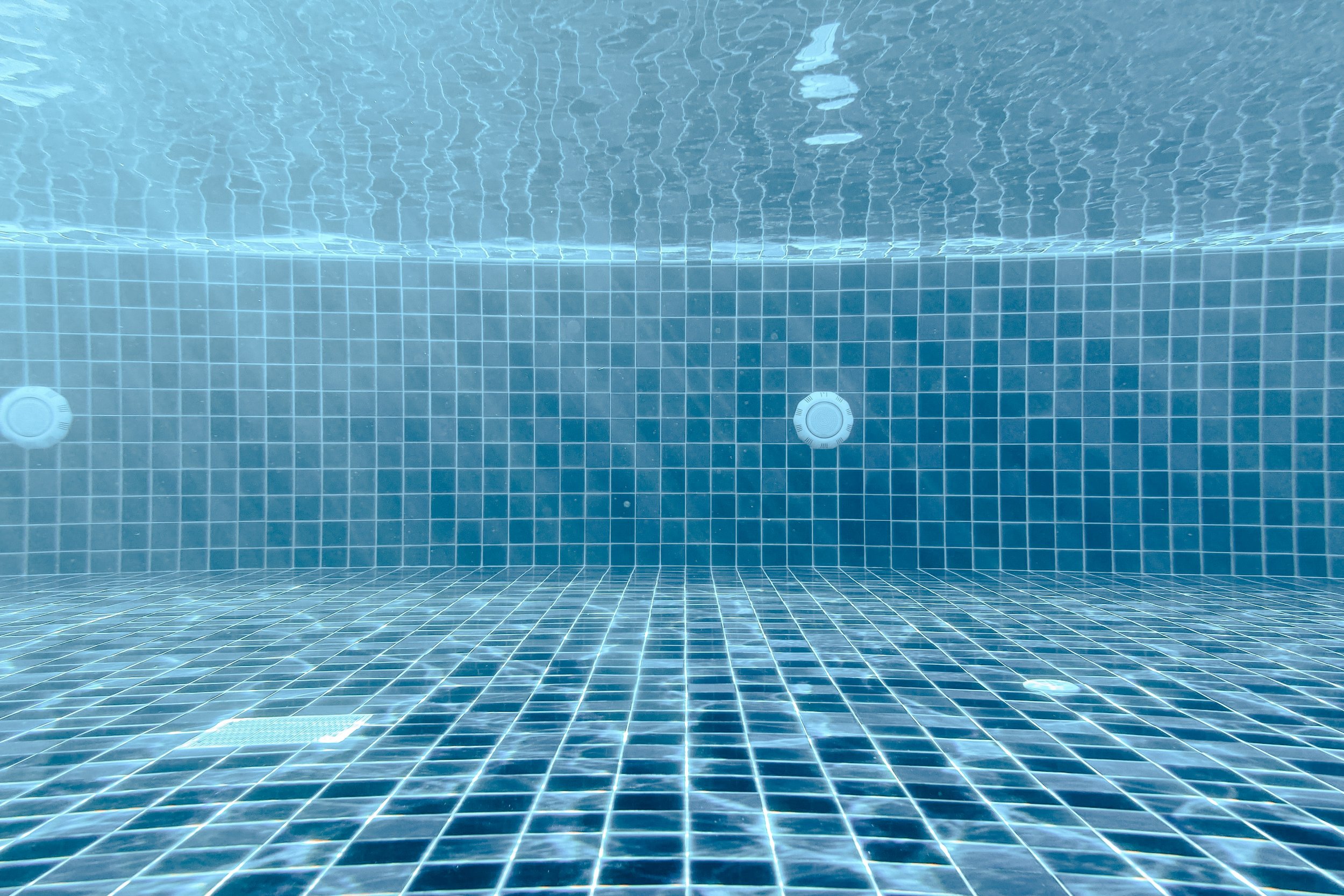

The summer I turned seven, my grandfather taught me how to swim in our overcrowded local pool in Beijing. Every afternoon, he would put me through the drill of catch, pull, flutter kicks. He learned to swim in the ‘70s from the natives on the island of Zanzibar off the coast of Tanzania, while working as a diplomat facilitating the construction of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway.

I had always felt a strong connection with my grandfather, even an ocean away from him. But for the first month after he died, I couldn’t feel his presence. It wasn’t until I picked up swimming again at my local aquatics center in Australia that I started to regain that sense of connection. As my arms sliced through the water’s prismatic shimmers, I felt the current of an interminable history flowing through my body. It occurred to me that our bond predated my existence; it had begun with my grandfather’s friendship with the natives of Zanzibar, who taught him the skill he would impart to me years later. That friendship shimmered in each stroke I made through the water. I felt a renewal, a metamorphosis in my relationship with my grandfather: the responsibility to keep his story alive, even if no one else was around to remember.

Contemporary grief culture is fixated on healing and finding closure with little regard for the emotionally vulnerable, for whom “moving on” may be an act of violence. Elegy resists that violence by affirming the continuity of our relationships with the dead. It allows us to maintain or transform those relationships on our own terms. It means singing to an absence and believing that absence can eventually be willed into presence. Elegy is the séance we hold as we pray for a visitation from the ones we have lost. We invite them to haunt us. We sing to them, and listen for song in return.

Gavin Yuan Gao’s “The Maestro,” along with twenty other pieces by contributors and two columns by the Half Mystic team, are compiled in Half Mystic Journal’s Issue X: Elegy, a constellation of contemporary art, lyrics, poetry, and prose dedicated to the celebration of music in all its forms. Issue X is a prayer against forgetting, a promise to bear witness even where music falls short. And when the time comes to let go of what it can’t live without, the elegy issue knows what it means to wake into memory. It knows that in a world touched by song, there exists no such thing as extinction. It is available for preorder now.